If you haven't seen The Room, you're fortunate. It is not so much a film as it is an experience and it is not a pleasant experience. While not quite as cringe-inducing as The Human Centipede or its' sequels, The Room is equally uncomfortable to watch. To watch The Room is to stare into the heart of madness itself - a chaotic, Lovecraftian madness that goes by the name of Tommy Wiseau.

Wiseau is a man who - had he not been born - would have to be created by Sacha Baron Cohen. The kindest adjective that might be applied to Wiseau is eccentric. Independently wealthy through mysterious circumstances, Wiseau has been notoriously evasive about his origins since achieving infamy through his film. The Disaster Artist does not make Wiseau's past any clearer but it does explain his motivations somewhat.

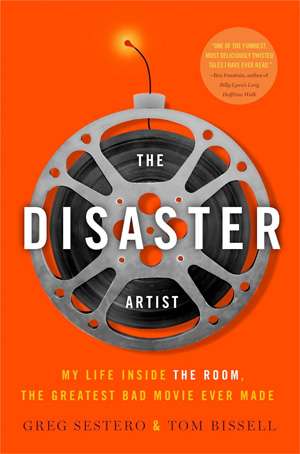

Co-written by Greg Sestero, who played Mark in The Room in addition to serving (unwillingly) as the movie's Line Producer, The Disaster Artist alternates between two points-in-time. Told in alternating chapters, half the book is devoted towards the downward spiral that was the making of The Room. The other half is devoted towards detailing Sestero's life as a young actor in Southern California and how he befriended Wiseau.

Cult film fans will doubtlessly be interested in reading about Wiseau's process or lack thereof. There is all manner of trivia regarding the shoot, like how Wiseau constructed a roof-top set with green-screen backgrounds in a parking lot rather than using an actual rooftop. Despite this, the alternating chapters about Wiseau the man and his friendship with Sestero offer far more insight into Wiseau The Artist than anything else.

Sestero and co-author Tom Bissell paint Wiseau as an overgrown man-child - a poor little rich boy who never learned how to make friends and tried to buy the life he wanted. This seems as likely an explanation as any for many scenes in The Room that serve no purpose other than to establish Tommy's character Johnny as a popular, well-respected man - i.e. the sort of man Wiseau wishes he was but is incapable of being due to his crippling insecurities and control issues.

There lies the grand irony of this book. By exposing Wiseau at his most inhuman, Sestero inspires sympathy for the devil. Wiseau's antics on the set inspire pity rather than outrage as one senses he really doesn't know any better. Likewise, Sestero himself manages not to come off as a back-stabbing opportunist even as he lays his relationship with Wiseau bare. He is quick to praise Wiseau for his generosity and notes that Tommy gave him the emotional support Sestero's family didn't as he was trying to make it, thus taking the edge off when he tells tales of Wiseau's legendary miserliness on the set and his numerous breakdowns off of it.

While it's not worth reading more than once, The Disaster Artist is worth picking up at the library. It has a lot to offer whether you're a fan of cult cinema, an aspiring actor interesting in reading about another actor's attempts to make it or the sort of person who slows down to look at the car crashes on the side of the freeway. Aficionados of The Room may be disappointed there is less about the film than there is about the people behind it but they can easily skip half the book if it bothers them that much.

No comments:

Post a Comment